By Claire Bradach

The Museum of Modern Art, now an iconic cultural institution of New York, was established in 1929. The MoMA’s photography department was founded in 1940, and the first two decades of the museum’s life reflect the debates surrounding what photography should be included in the museum’s collection and exhibitions. A critical turning point occurred in 1947, when Beaumont Newhall was ousted from his position as curator of the Department of Photography and replaced by Edward Steichen, a man Ansel Adams called “the anti-Christ of Photography.” This shift in leadership within the MoMA’s photography department was representative both of shifts within the MoMA more broadly and within the world of New York at the time. Beaumont Newhall, Nancy Newhall, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and Ansel Adams, advocated strongly for avant-garde art, while Edward Steichen and the Rockefellers were more mindful of the museum’s finances and therefore tended to be more conservative in their artistic sensibilities in the interest of not offending any potential museum patrons.

To put the feud between Beaumont Newhall and Edward Steichen into context, a few historical facts should be established. The Museum of Modern Art sought to become a leading authority on modern art, curating a collection of the best artwork from a variety of mediums. The goals for the museum laid out by the seven founding trustees were very vague at first. In a membership document, they wrote,

Our ultimate purpose is to establish a permanent public museum in this city which will acquire, from time to time, (either by gift or by purchase) collections of the best modern works of art. The possibilities of such an institution are so varied and so great that it seems unwise now to lay down too definite a program for it beyond our present one of a series of frequently occurring exhibitions during a period of at least two years (Bliss, Crane, Crowninshield, Sachs, Sullivan, Rockefeller, Goodyear, quoted in Bee and Elligott, 27).

Despite the vagueness of these goals, the museum administrators were able to establish the museum’s role as a major player in the New York art world from very early in MoMA’s history. The museum first focused on painting and sculpture, but over the years, new departments were added as the public or members of the museum administration embraced new mediums of art.

To take another step back, MoMA can be understood as a champion of the avant-garde in New York during and after World War II, and the focus on photography is just one way in which this championing occurred. The New York art scene generally tended toward the avant-garde in this period, with the rise in abstract expressionism being a prominent product of this movement. On this subject, Serge Guilbaut writes, “After the Second World War, the art world witnessed the birth and development of an American avant-garde, which in the space of a few years succeeded in shifting the cultural center of the West from Paris to New York” (Guilbaut, 1). Avant-garde as a movement worked in harmony with the Communist party and was seen as a refreshing contrast to Parisian nationalist art. Guilbaut notes the significance of Samuel Kootz in this movement, as Kootz “challenged the New York art community to react to the death of Paris by creating something new, strong, and original. This was the moment for New York to gain its freedom from both Paris and reactionary nationalist art” (Guilbaut, 64-5). The impulse to stray from painting and delve into novel mediums was one way in which Kootz’s call for new art played out, which may partially explain the popular demand for photography in this historical moment in New York. Kootz himself became a member of MoMA’s advisory board, which suggests that the museum shared his positive feelings toward the avant-garde (Guilbaut, 121). Within this context of the American avant-garde, it makes sense that the MoMA aligned itself with the movement, and that the emphasis on photography was a side effect of this orientation.

To further contextualize the MoMA’s shift toward the acceptance of photography, it is also important to understand the contributions of Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the museum’s founding director. With his vast network of connections in the artistic and literary world, Barr rallied support for the museum in its early years from many sources. He made several trips to Europe to meet artists there and to experience the European artistic and cultural hubs of Paris, Berlin, and Prague. Barr made his way into the art world by becoming a professor of history of art at Vassar College, where he arranged an exhibition called “Exhibition of Modern European Art” in the campus art gallery (Roob, 5). He borrowed works from New York galleries, and Barr made several important connections with art dealers through soliciting paintings for the exhibition (Roob, 5). Barr later taught at Wellesley College, where he had the opportunity to develop his own course on modern art (Roob 8-9). Through his teaching and his publications at the time, Barr began to develop a reputation as a champion of modern art, and eventually gained enough acclaim to be able to travel around Europe visiting artistic heavyweights of the time, including Giacomo Balla, Piet Mondrian, Alberto Giacometti, André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, and others (Roob, 30-48). Barr’s influence on the art world was widely accepted, and his artistic visions for the museum in its early years were thus very important in shaping MoMA. Barr’s connections with artists, as well as his visions for a leading modern art museum, had tremendous influence on MoMA. As Barr himself stated, he was responsible not only for the creation of exhibitions and catalogue that elicited money and prestige for the museum, but also for his “effort from the beginning to keep alive and then develop the idea of a great collection” (Barr, A., quoted in M.S. Barr, 72). His role as a strategist and visionary played integral roles in making MoMA the grand institution it still is to this day.

Leaders in the MoMA’s administration did not recognize the importance of photography in the very early years of the museum, but the popularity and demand for photography soon grew to the point where it was deemed necessary to have an entire department devoted to the medium. Early museum records reflect the relative lack of importance photography had in the collection. In a 1936 MoMA bulletin, photography was mentioned briefly in a section called “Other Arts” (MoMA, “Some Books”). The museum founded departments devoted to film in 1935, architecture in 1932, and Industrial Art in 1933 (Goodyear, 11), suggesting that the museum was slow to recognize the importance of photography even after branching beyond the traditionally accepted media of painting and sculpture. However, by the late 1930s, the museum recognized public demand for photography. In one 1939 MoMA bulletin in which administrators reflected on the first ten years of the museum, Paul J. Sachs wrote,

If we review the extraordinary achievements of our first decade here we are not surprised to find that the primary interest of the trustees has been in painting, sculpture and the graphic arts. If, however, we pay attention to the attitude of the rising generation it seems clear that in the coming decade energy and funds must be allocated with enthusiasm on a larger scale to films, to architecture, to photographs and to the library; for it is through these that the greatest number of young people can be reached:—a fact, I fear, which too few of our generation appreciate” (Sachs, 8, emphasis in original).

In this, Sachs explicitly acknowledges the “rising generation” and its demand and appreciation for photography. This statement serves as a public commitment, which, indeed, was realized, to devote more resources to photography (and other mediums), in order to meet public demand. Although museums traditionally see themselves as arbiters of what is considered art, the MoMA proved in this instance, and in many others, to take its audience into account when making grand strategic decisions. An explanation for this could be that the museum had its own financial well-being in mind when expanding its collection to include these new mediums. Sachs recognizes that the current generation may not appreciate film, architecture, or photography, but by investing in these mediums, the museum was able to ensure its own survival as its young audiences aged. The allocations of funds can be said to be a result of both a wise use of the photography experts employed by MoMA and a forward-thinking pragmatic decision.

Documents of the era capture public interest in photography in a variety of ways. In addition to the museum’s stated acknowledgement about the “young people” who want photography to be represented in modern art collections (Sachs, 8), museum attendance records and media coverage reflects the growing interest in the medium. The museum reported that the attendance for Beaumont Newhall’s Photography 1839-1937 exhibition was 30,429, which was relatively high in comparison to other exhibitions of the time (MoMA, “Annual Report”). The only exhibition of the 1936-1937 museum year that had higher attendance was the Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition, which drew an audience of 50,034 people (MoMA, “Annual Report”). None of the other exhibitions had attendance higher than 20,100 people, which underscores the impressive size of the crowd that the photography drew. Photography proved to be popular after the creation of the department. The Family of Man exhibition, organized by Steichen in 1955, broke museum attendance records (Hunter, 29), and other patriotic photography exhibitions held by MoMA were wildly successful as well. The MoMA’s expansion of its photography programs as early as the early 1930s showed powerful perception of the public’s demands.

The emphasis MoMA came to place on photography set it apart from other museums (both American and international) of the era. A history of the Metropolitan Museum of Art acknowledges that the MoMA had a more extensive collection of twentieth-century art, including photography. The Met was less interested in this era of art than MoMA and therefore allowed MoMA to become the leading authority on 20th-century art trends, including photography, Cubism, and Dada (Hibbard, 458). Guilbaut succinctly describes the differences in public perception between the institutions of the Met and MoMA: “The trustees of the Met represented old wealth in America, and the museum consequently stood for a tame, prudent, and academic culture oriented toward the past. Young, literal, and dynamic, the Museum of Modern Art represented new wealth, the ‘enlightened rich’ (Rockefeller, Such), the future of American culture” (Guilbaut, 76-7). Alfred H. Barr, Jr. noted the uniqueness of MoMA’s emphasis on photography within New York institutions in his writing that accompanied the 1939 Art in Our Time exhibit, which celebrated the tenth anniversary of the museum and the opening of the new MoMA building. Barr wrote,

“Art in Our Time” presents achievements of living artists together with the work of certain important masters of yesterday. It differs from the special exhibitions of modern art in other New York museums at the time of the [New York World’s] Fair by its inclusion of foreign work as well as American, and by its concern not only with painting, sculpture, and the graphic arts but also with architecture, furniture, photography and moving pictures (Barr, A., “Art,” 13).

This description makes clear that the museum identified as a leader among its peers with respect to prominently displaying photography, even though it had not yet formalized this prowess into a specific department. The MoMA also differed significantly from the Guggenheim, which opened in 1942. Guilbaut places Peggy Guggenheim in the middle of the movement toward the avant-garde and novel, which was, to reiterate, also represented in the MoMA’s emphasis on the relatively new medium of photography. Despite this ideological similarity, however, people at the time viewed the Guggenheim collection as a product of Peggy’s “erratic” tastes, which she bolstered by “surround[ing] herself with a battalion of experts including Herbert Read and Marcel Duchamp, a majority of whom (such as Sweeney, Barr, and Soby) were affiliated with the Museum of Modern Art” (Guilbaut, 68). This reading suggests that by the early 1940s, the public already viewed MoMA as a credible arbiter of taste within the world of the avant-garde in New York.

Documents from this era suggest that the MoMA was a leader in displaying photography among its international peers as well. In 1938, the museum shipped a collection of what it considered quintessentially American art to Paris to be displayed at the Musee du Jeu de Paume under the name “Exhibition of the Art of the United States” (Barr, A., “Foreword”). Beaumont Newhall curated the photography portion of the exhibition. Museum director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. noted that, “The inclusion of architecture, photographs, and cinema in addition to painting and sculpture is a radical departure from the usual exhibitions of national art arranged by other countries in Paris.” (Barr, A., “Foreword”). This diversity of mediums that the MoMA embraced from relatively early in its history set it apart from other museums even in Paris, a city widely regarded as the international capital of art at the time. As MoMA put more resources into its photography collection, a trend most obviously codified in its decision to create a formal department around the medium, this distinction from other museums became even more vivid, solidifying MoMA’s position as a leading expert in photography.

Despite the combination of inclusion of progressive art and established reputation that set MoMA apart from its peer institutions, the administration began to seek the severance of figures within its ranks who typified the liberal avant-garde in the late 1930s. Beaumont Newhall; Alfred H. Barr, Jr.; John McAndrew, head of the Department of Architecture; museum president A. Conger Goodyear; Francis Collins, head of publications; and Tom Mabry, secretary of the museum were all ultimately replaced or demoted over the course of a few years (Barr, M.S., 55-58). Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who was abroad in Europe at the time of many of these announcements, was shocked, and his wife, Margaret Scolari Barr, recounts that she and Alfred were “stunned” (Barr, M.S, 55). Margaret explains further,

In early spring [of 1939], Nelson Rockefeller, in preparation for his appointment as the new president, had called in some ‘efficiency experts’ to analyze the workings of the museum. They could not make out what its purpose was, nor how it went about its business. They were bad news, but A. had not foreseen the consequences of their reports. Now, Nelson Rockefeller has bypassed A.’s authority as director of the museum and has played havoc with its nervous system (Barr, M.S., 55-6).

This instance occurred years before Barr was himself to be ousted from his role as director, but it proves a moment of foreshadowing. The Rockefellers, as funders and trustees of the museum, wielded a tremendous amount of influence over staffing and other decisions, and it appears that they made these particular staffing decisions and others based on “efficiency.”

The forced personnel changes in the 1940s made it very clear that the trustees had visions and goals for the museum that differed from those of some of the people that made the museum’s success possible. Specifically, the decisions of the trustees to remove Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and Beaumont Newhall demonstrated the trustees’ conservative artistic tendencies and their focus on finances. Barr was fired on October 13, 1943. In a biography of Barr, Sybil Gordon Kantor writes, “Barr had been having difficulties for the preceding six years on a variety of fronts: his taste was running ahead of the trustees’, his writings were always behind schedule, and, in the area of administration (which he disliked), competing forces were undercutting his efforts” (Kantor, 354). The ideological differences between Barr and other important figures within the MoMA administration can be traced back to the very beginning of the museum, to Barr’s statements about his vision for the museum before its creation. In his first prospectus for MoMA, Barr originally mentioned photography explicitly in his plan for a “multidepartmental museum,” but the explicit reference was deleted in the final draft, which read, “In time the Museum would expand to include other phases of modern art” (Roob, 19). One might conclude that Barr’s ideas for the museum were more progressive, while others within the administration tempered his enthusiasm with demands that he respect financial constraints and possible public conservatism. Kantor notes that the ideological issues between Barr and other museum administrators also emerged when Barr’s inclusion of several bold surrealist pieces, including Meret Oppenheim’s fur-covered teacup, saucer, and spoon, offended the sensibilities of certain figures of the museum who did not believe the piece to be art at all (Kantor, 356-7). This perceived faux pas on Barr’s part led museum administrators to worry that Barr’s tastes were too bold for their audiences and might drive people (and their money) away.

Trustees also made more explicit references to their frustration with Barr’s lack of productivity when they announced the decision to fire him. The museum’s reputation and financial success was deeply intertwined with Barr’s scholarly work, so they had little use for him when he was not producing writing (in addition to when he was running the risk of offending museum patrons). Stephen C. Clark, the chairman of the board of trustees, particularly took issue with Barr’s slowness in writing, as “the trustees had materially gained from the worldwide reputation Barr had secured for the Museum from his catalogues and exhibitions” (Kantor, 360). In the face of this confluence of issues, Abby Rockefeller, who had been on Barr’s side in the early years of the museum, came to admit that she would prefer MoMA to be led by someone more able to bolster the museum’s finances. She wrote to A. Conger Goodyear, “We should from now on have a director who directs. One who has the confidence and sympathy of the trustees and who is able to help raise money, as well as interest people in giving their collections” (Rockefeller, quoted in Kantor, 357). Barr was appalled by the callousness shown in the suggestion that he step down and by a letter Rockefeller wrote to him, in which she suggested that he was better off being demoted. Margaret Scolari Barr noted, “He is more hurt by this than he was by Clark’s letter” (Barr, M.S., 69). Alfred H. Barr was ultimately allowed to stay on at MoMA as director of collections—a smaller role, but one in which he succeeded. The demotion, however, serves as evidence of the administrators’ abiding economic pragmatism.

This same pragmatism can be seen in the decision to let Beaumont Newhall go in favor of Edward Steichen. Like Barr, Ansel Adams and Beaumont Newhall advocated for the inclusion of photography at MoMA from its early days. In 1935, the two men discussed the state of photography in America, and Adams “stated then that photography had become sufficiently mature both as an art form and as a medium of communication that it warranted an institution dedicated to exhibiting the best work and supporting future growth” (Spaulding, 175). Newhall began working at MoMA as the museum librarian in 1935. Although his job did not entail photography at first, Newhall published scholarship on photography while working as a librarian, and his growing reputation within the photography world attracted the interest of MoMA administrators (Spaulding, 148). Spaulding narrates an interaction between Newhall and Barr that highlights the interest the two men shared in photography: “’Alfred could see I was really keen on photography,’ Newhall recalled, ‘and one fine day he stopped me in the corridor and asked me, “Would you like to do a photographic show?” I said I most certainly would.’” (Spaulding, 148). The opportunism of MoMA administrators shines through in this anecdote. The higher-ups wanted to capitalize on public interest in Newhall’s work by giving him a larger role that would be likely to draw his already-formed audience to the museum. Newhall was then assigned to create a broad exhibition of photography that would demonstrate both the history of the medium and contemporary works (Spaulding, 148). This idea would come to fruition with the Photography 1839-1937 exhibition, which featured the works of Adams and other contemporary photographers, like Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray, as well as photographers whose work exemplified old techniques of photography, such as daguerreotypes and wet plate photography (MoMA and Newhall, 97-115). A history of MoMA recounts that this exhibition was very popular at the time: “An extraordinary public response had greeted the Museum’s first exhibition featuring photography as art” (Hunter, 24). This exhibition was critical to the solidification of MoMA’s authority on the subject of photography and to the establishment of a canon of notable photography. Clearly, the museum’s decision to use Newhall’s photographic knowledge, for which he was already widely acclaimed, for the creation of this exhibition paid off financially and reputation-wise for MoMA.

Even more important to museum trustees, however, may have been the connections that Newhall brought to MoMA that allowed for the creation of the photography department. An article written after Newhall’s death noted:

Ansel Adams had become a great friend of the Newhalls and it was he who introduced David H McAlpin, a New Yorker, who raised the funds to start the photography department at MOMA which Newhall ran. It is an irony that Newhall was fired after his return from the war in favour of Edward Steichen. It was felt by the directors that Steichen’s name would bring in the big money (McCabe, 1).

This sheds interesting light on the reasons for hiring and firing Newhall. It would seem that, despite Newhall’s tremendous contributions to the museum and to the medium of photography and photographic scholarship, museum trustees took heed of financial considerations more than they made decisions based on these academic accomplishments. Due to his connections and the popularity of his 1937 exhibition, Newhall was strategically important to the museum in the 1930s, which led to his hiring and to his continued employment through the end of the ’30s, but he was seen as no longer as profitable in the 1940s, and therefore was viewed as dispensable.

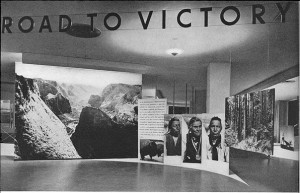

In the 1940s, Edward Steichen emerged as a figure within the museum who was able to garner popular acclaim for his photography exhibitions as Newhall had in the ’30s, which made him a valuable asset to MoMA. Steichen’s 1942 exhibition, Road to Victory, was one of several patriotic exhibitions MoMA hosted. Hunter writes, “It was undoubtedly the most overtly political exhibition held by the Museum during the war years and received enthusiastic notices, often highly emotional in tone, in the major American newspapers. The New York Times, for example, called the exhibition ‘the supreme war contribution’ and ‘the season’s most moving experience’ (Hunter 24). In the wartime era, Steichen’s sensibilities aligned more closely with those of the American public. The popularity of the exhibition, seen in the rave reviews and in museum attendance numbers, provided the museum with a financial boost. The exhibition also served as a landmark in terms of its novel display tactics. The exhibition was organized in a “procession” in which the photographs presented the story of America and its wholesome values, followed by representations of the global influences that made war necessary (Staniszewski, 212). This narrative strategy proved wildly popular and stands in retrospect as a major turning point in the history of art installation. Hunter describes, “The theatrical installation marked a new era in photographic presentation, with monumental photomurals of America and its people set off by rousing appeals for sacrifice and dedication in texts by poet Carl Sandburg.” (Hunter, 24). As a result of this artistic innovation and intensely favorable public reception, Steichen was hired as the head of the photography department, in large part because of the museum’s faith that he could continue producing popular, lucrative exhibitions. The trustees’ faith appears to indeed have been well placed, as Steichen organized similar patriotic, well-received shows during his tenure as head of the department. Hunter notes that he “organiz[ed] a number of large spectacular exhibitions with broad public appeal. He was most successful with his 1955 exhibition The Family of Man, which was seen by more than nine million people in the United States and abroad when it traveled, and which broke all Museum attendance records at home” (Hunter, 29). This success justified the museum administration’s decision to replace Newhall with Steichen, as Steichen garnered precisely the sort of popular exhibitions that the trustees were seeking.

Beaumont Newhall and Ansel Adams were outraged by MoMA’s decision to replace Newhall with Steichen, as they thought Steichen’s patriotic exhibitions were clear examples of what they perceived as a general trend of Steichen’s preference for overly showy and inartistic photography. Adams also had a personal distaste for Steichen that originated in their first interaction. Adams writes in his autobiography, “Edward Steichen and I were at swords’ point form the moment we met in 1933” (Adams and Alinder, 207). He explained that Steichen twice broke Adams’s appointments to see him, and writes, “I felt his arrogance, not because he was too busy to see him, but because of his manner of disdain and his abiding sense of power and prestige” (Adams and Alinder, 207). In addition to taking issue with Steichen’s personality, Adams found Steichen’s artistic preferences distasteful. Adams made his disgust with Road to Victory very publically known, even going so far as to suggest that the exhibition was not photography at all:

He thought the exhibition belonged in Madison Square Garden rather than in the Museum of Modern Art. Steichen, he felt, was more concerned with theatrics and attracting a huge crowd than with photography as a serious art form. Steichen’s liberties with photographic print quality were a particularly irksome point to Adams. He thought the huge enlargements were amateurishly produced, with a grainy texture and a limited range of values, all muddy grays. He felt the exhibition was not about photography at all; it was a bombastic harangue that happened to use the medium of photography to achieve its goals (Spaulding, 198).

Adams bemoaned the lack of artistry and attention to detail of Road to Victory, but it remains that Steichen was very perceptive about what the American people wanted to see. Spaulding writes, “Steichen brought with him a theatrical approach to exhibitions that Adams found inappropriate to an art museum but proved immensely popular with the general public” (Spaulding, 103). Ultimately, this popularity with the general public was precisely what the museum wanted. Adams’s qualms about Steichen’s taste, which may or may not have been exacerbated by the men’s personality clashes, did not matter to the museum’s trustees, who were primarily interested in creating exhibitions that the people would enjoy.

Clearly, Newhall and Steichen are both extraordinarily accomplished individuals in the field of photography. The MoMA benefitted largely from these men’s work at the museum. Newhall’s achievements are recognized to this day as being foundational to the field of photography. Hunter writes, “He established intellectual and professional standards that remain cogent for the curatorial field that he in large measure founded” (Hunter, 465). To this day, Newhall is considered a defining figure of American photography, and a large portion of his career was deeply intertwined with MoMA. Similarly, Steichen was praised for his ability to organize exhibitions that deeply resonated with the American people. These accomplishments, however, were not of primary concern when the MoMA made its personnel decisions. The museum trustees wanted to build the finances of the museum, and they wanted the photography department to be run by the person who, at any given moment, seemed most likely to be able to generate revenue. In the 1930s, this was Beaumont Newhall, but by 1947, Edward Steichen seemed to be the man most fit for the job. The artistic accomplishments of both men stand out to people of the present day, and likely did for Newhall and Steichen’s contemporaries, but it is clear that MoMA trustees also had a very strong interest in the men for what they could provide the museum financially as MoMA worked to become the institution it is today.