[vimeo]https://vimeo.com/115233641[/vimeo]

Balcony Seats at a Murder

a course on the the literary and cultural history of NYC in the golden age of the 1940s

By Lily Taylor

Pete Seeger, born to two highly musical parents, grew up in a house full of instruments, so deciding which one to play was not easy. When Pete asked for advice on this matter, his father decided to plan a trip to take Pete to Asheville, North Carolina to see a folk musician named Lunsford play the five-string banjo.[1] “The Seegers “loaded up their big blue Chevy and headed South to meet “the folk.”[2] Seeger, a kid who went to boarding schools in New England for his entire childhood, was in awe of the vitality and authenticity of both folk music and culture, especially in comparison with the cheesy pop music he was used to in the northeast.[3] Lunsford lent Pete his five-string banjo, and over the course of Pete’s career, that seemingly exotic kind of banjo would become nearly synonymous with the name Pete Seeger.

By Claire Bradach

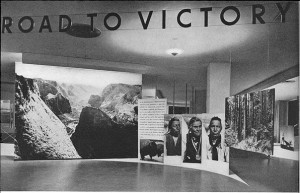

The Museum of Modern Art, now an iconic cultural institution of New York, was established in 1929. The MoMA’s photography department was founded in 1940, and the first two decades of the museum’s life reflect the debates surrounding what photography should be included in the museum’s collection and exhibitions. A critical turning point occurred in 1947, when Beaumont Newhall was ousted from his position as curator of the Department of Photography and replaced by Edward Steichen, a man Ansel Adams called “the anti-Christ of Photography.” This shift in leadership within the MoMA’s photography department was representative both of shifts within the MoMA more broadly and within the world of New York at the time. Beaumont Newhall, Nancy Newhall, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and Ansel Adams, advocated strongly for avant-garde art, while Edward Steichen and the Rockefellers were more mindful of the museum’s finances and therefore tended to be more conservative in their artistic sensibilities in the interest of not offending any potential museum patrons.

Lisette Model, “Running Legs, 5th Ave., New York” Hi, and welcome to ENGL 284: New York City in the 1940s (Fall 2014). For students enrolled in the course, I’ll be using this blog to post occasional interesting materials and information about some of the historical context for our reading and viewing. Come the end … Read more

W. H. Auden was one of the major literary personages in New York in the 1940s. He was highly influential on his contemporaries, but he was also representative in some ways of the intellectual and political journey that many of his contemporaries took over the course of the latter thirties and 1940s.

The publication of John Hersey’s Hiroshima was a significant event in the history of American journalism and also in the history of the magazine in which it first appeared–The New Yorker. Hersey’s chronicle was a sensation when it appeared, as the entire editorial contents of one issue. (For more information on this famous issue, see this older post.) In addition to marking the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, the event signalled the new stature that The New Yorker had assumed over the course of WWII. The magazine had now become a defining voice of postwar, metropolitan liberalism.

Last week I mentioned that Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn probably owed some of its success to the fact that the book had been published in an Armed Services Edition and was one of the 1300 such books that were distributed for free to members of the military during WWII.

The other day in class we briefly discussed Weegee and his distinctive way of depicting New York city in the 1930s and ’40s. Walker Evans gives us a somber, underground world, and his portraits show us usually solitary, often introspective and frequently bedraggled looking New Yorkers. Weegee, by contrast, portrays a vivid and dramatic–or, perhaps, melodramatic–city.

Rick has sent along some fascinating info about a key backstory for On the Town. Apparently, the Paul Cadmus painting above was the original inspiration for the Jerome Robbins ballet Fancy Free, which gave rise to the Bernstein-Comden-Green-Robbins Broadway production of On the Town, later to be adapted for the Hollywood Stanley Donen/Gene Kelley movie version.